Creating a gentrified guilt complex (op-ed)

|

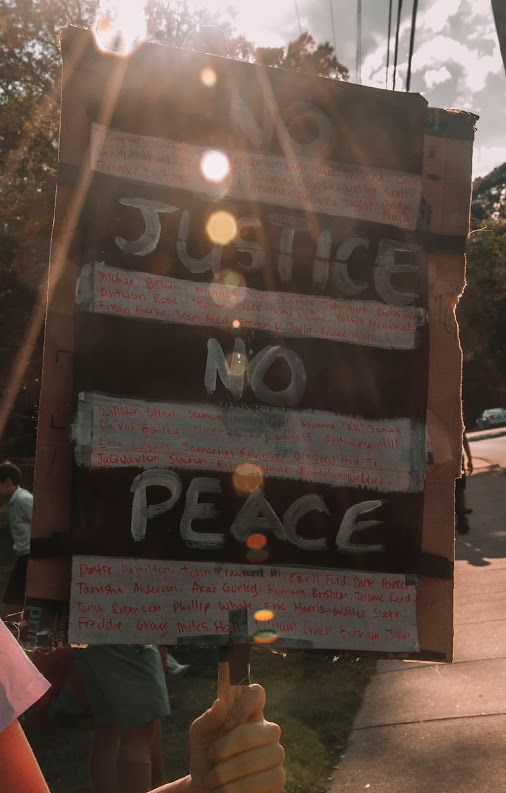

| Photo by Maria Oswalt on Unsplash |

In

2006 author Shelby Steele published, White Guilt: How Blacks and Whites

Together Destroyed the Promise of the Civil Rights Era. Steele described white guilt as the vacuum of

moral authority that comes from simply knowing that one’s race is associated

with racism.

Therefore,

whites (and American institutions) must acknowledge historical racism to show

themselves redeemed of it, but once they acknowledge it, they lose moral

authority over everything having to do with race, equality, social justice, and

poverty. The authority whites lose

transfers to the “victims” of historical racism and becomes the victim’s source

of power in society. Steele

went further: Anger is not inevitable for the oppressed; it is chosen when

weakness in the oppressor means it will be effective in winning some kind of

spoils. Anger in the oppressed is a

response to perceived opportunity, not to injustice. Injustices create only the potential for

anger, but weakness in the oppressor calls out anger, even when there is no

injustice. In both the best and the

worst sense of the word, black rage is always a kind of opportunism. Last

month, in Kentucky, Black Lives Matter Louisville, created a social justice

rating system to grade establishments in the NuLu Business District. Grade A = Ally, meaning the establishment

supported black liberation and met the requirements. Grade C = Complicit, meaning the

establishment failed to meet 2 or more of the requirements. Grade F = Failure, meaning the establishment

failed to meet minimum requirements including failure to create a safe space

for black inclusion. The requirements,

which were actually social justice demands, were the following: 1).

Establishments must have 23% BIPOC on staff 2).

Establishments must receive 23% of inventory from BIPOC businesses 3).

Establishments must make regular donations to BIPOC organizations 4).

No dress codes that discriminate against BIPOC patrons or employees. The

activist expected NuLu business owners to sign a contract that stated: I, a

business owner in the gentrified NuLu Business District, understand that

gentrification targets poor and disadvantaged communities of color. I acknowledge that the original residents of

Louisville’s Clarksdale community, which was demolished to make way for NuLu,

have been harmed by displacement. I

acknowledge that my business has played a part in the harm done to Clarksdale’s

original residents, who have received no economic benefits from our occupation. The

reaction from NuLu’s business owners ranged from weak, to mild, to

extreme. Some owners believed they had a

responsibility to admit gentrification occurred and they should play an active

part in increasing diversity in the district.

Other owners felt the activists had a legitimate grievance, but

disagreed that the NuLu district was part of the gentrification that took place

at Clarksdale. Then there were owners

that insisted that the activists were using mafia shakedown tactics to achieve

their goals. In response to the last

group of business owners one activist warned, “How you respond to this is how

people will remember you in this moment.

You want to be on the right side of justice at all times.” Another

social justice demand centering around gentrification happened earlier this

month in Seattle. The Seattle Times

reported that Seattle was the third most gentrified city in the United States. The city’s Central District has seen a

dramatic drop in black residents. The

paper estimated by the next decade the Central District will be 10 percent

black, down from 73 percent black in 1970.

A small group of Black Lives Matter activists went on a march to demand

for white people to give up their homes as a form of reparations for

gentrification. Ta-Nehisi

Coates’s 2014 article The Case for Reparations contained a list of historical

grievances in the subtitle: Two hundred fifty years of slavery. Ninety years of

Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate but equal. Thirty-five years of racist

housing policy. Then Coates wrote: Until

we reckon with our compounding moral debts, America will never be whole. These

activists just added gentrification to America’s compounding moral debt and

will continue to guilt the present in an effort to gain from the past. First

published in the New Pittsburgh Courier 8/26/2020 |

Comments

Post a Comment